Programming Uncertainty and Self Doubt

My Instagram feed is filled with posts from strength coaches. Everyday, these coaches post new exercises and workout plans. Some accounts offer their content as something to consider. Others promote a silver bullet that addresses exactly what you’ve been missing. Depending on your mindset, these types of posts can be toxic. They can cause self-doubt and anxiety: “Shouldn’t I follow the advice of an expert? But how can I fit this into my current programming? How can I fit the advice from hundreds of posts into my programing?”

The comparison between yourself and the perfection in the post makes them difficult to ignore. Even the experienced athlete may be gullible - the reward is so great that it’s worth trying. However, these accounts may post multiple times a day, and the constant scrutiny of your programming can be exhausting. Exposure to new methods is a key to self-improvement, but there must be a way to manage the breadth of the available information. Reevaluating the general concepts of programming (periodization) may be a part of the solution.

What is Periodization?

In the most simple terms, periodization can be thought of as the strategic planning of future workouts. The planning is usually not an issue, but the rigidity of the plan can be. Sometimes programs are planned days or weeks in advance without room for adjustments. For example:

- Week 1 - 80% 1 RM 5x5 Squat

- Week 2 - 85% 1 RM 5x5 Squat

- Week 3 - 95% 1 RM 5x5 Squat

- Week 4 - 60% 1 RM 5x5 Squat

This plan can work, but doesn’t allow the athlete to provide feedback. It seems that a better approach would be to incorporate emergent information into the plan as it becomes available (fatigue status, nutritional state, etc.).

Homeostasis vs. Allostasis

The predominant periodization theory is centered around homeostasis, which states that the body tries to maintain a steady-state. A specific stimulus will elicit a specific response. Homeostasis assumes a high level of precision and predictability, and any deviation from the expected response must have a detectable cause. This type of thinking leads to the analogy of the human body as a car. A car is a fine-tuned machine. Any change made to the car will have a measurable response. Logically it makes senses that a car and human body could operate in the same way, but research has shown that individuals respond differently to the same stimuli, unlike a car. The body is a living thing and the aggregation of its processes may not be as predictable.

A contrary theory to homeostasis is allostasis. Instead of the certainty of the steady-state, allostasis describes a more a variable system. The body tries to anticipate its current and future needs by employing a number of neurological, biological, and immunological processes. The interplay between these processes means that a specific stimulus may elicit a different response depending on the individual. Someone may be emotionally stressed, genetically predisposed to certain adaptations , or even immunologically comprised, which can all impact the response to training. This is not to say that the effects of training are completely unpredictable, but allows for more flexibility to adjust workouts.

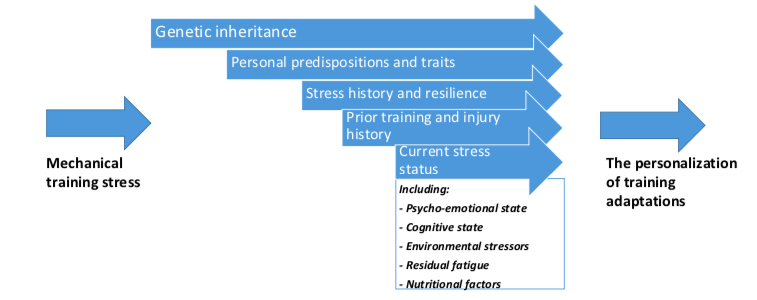

Above are factors that influence training from John Kiely’s 2017 article Periodization Theory: Confronting an Inconvenient Truth. Though these do not need to be examined for each athlete, coaches can consider these when evaluating an athletes response to training.

Programming Implications

Sports science research often considers the group average as the effect of a specific exercise; however, the individual responses are important too. The Heritage Family Study considered the effects of endurance training on VO2 max. The average increase in VO2 max was 19%, while individual responses ranged from 0% to >50%. While the average increase of 19% is exciting, we also have to keep in mind that individuals respond differently and training can be tailored to the individual to some degree.

So how can we make sense of traditional training methods and individuality? Creating a precise training program for each individual can be inefficient, and there is no guarantee of its success in the context of: 8 reps of a certain exercise is best for Athlete A while 6 reps is best for Athlete B (more individuality is appropriate in a 1-on-1 setting vs a team setting though). However, traditional training programs may be rigid and lack athlete feedback. One approach, especially for novices, is to begin with the a traditional program (e.g. Starting Strength 5x5 for strength training) and then adjust as needed. If the athlete is feeling too fatigued, the volume/intensity could be reduced. If the athlete is not making gains, the volume/intensity could be increased.

There are multiple variables to consider such as exercise selection, sets, reps, weight, time between sets, and rating of perceived exertion during each set. While experience can help coaches decide how to manipulate these variables, it is not unreasonable for coaches to rely on trial and error within reasonable limits. Coaches may have to be comfortable with the uncertainty and help their athletes understand the process.

Coaching Implications

At any level, an athlete may be seeking the optimal program for their body. They may constantly evaluate what they are doing and compare to online “experts” who advocate for many “best” exercises (“the 10 best exercises to build a bigger back”). While this information may be useful for someone who does not have much variety, the phrasing of the post may also give athletes anxiety. The following problems may arise: 1) the are an numerous posts about the best exercises and it is impossible for an athlete to fit all of these in during the week and 2) if the current exercises in the athlete’s program are not included on the “best” list, why is the athlete bothering with them. This can begin a vicious cycle of self-doubt for the athlete.

To combat this, coaches should prioritize conversations about these issues with their athletes. Reframing the athlete’s perceptions about the training process can be helpful. The athlete should understand that everyone is different. Responses to training are not as predictable as some may imply. There is no clear “best” exercise for anyone. The coach can present the current program as a base to work from and encourage the athlete to provide feedback and adjust as needed. There should be a process in place to gain this feedback, one that allows for open communication between coach and athlete and empowers the athlete to take ownership of his or her program. Without the proper support, the uncertainty around training can be demoralizing. When athletes better understand the training process, it can lead to more compassion towards themselves and reduce stress and comparisons to others.