Evaluation of the ACWR

Research around non-contact injuries has become increasingly popular. And for good reason. It seems that every few weeks, a high profile athlete suffers a devastating knee injury. As the athlete begins to change direction, she falls to the ground holding her knee, untouched by surrounding defenders. Medical staff rush on the field, while those in the stands have already diagnosed the ACL tear.

These non-contact injuries (ACL tears, hamstring strains, etc.) often leave athletes sidelined for significant periods of time, so clinicians have focused on risk factors and prevention strategies. These include analyzing foot strike patterns, femur lengths, sleep habits, and even surface “hardness”. One prominent theory has considered training workloads. If coaches regulate training workloads in a certain way, can they reduce these injuries? Specifically, the theory states that chronic training workloads are needed to build an athlete’s base, and acute workloads should not greatly exceed the chronic base. In order to quantify this concept, researchers have proposed the acute:chronic workload ratio (ACWR).

What is the ACWR?*

Simply, the ACWR is:

- weekly workload (past 7 days) / weekly workload (past 28 days)

Also, workloads are not strictly defined. Coaches can choose the most relevant EXTERNAL workload for their sport (e.g. # of meters run or # of pitches), while INTERNAL workloads are consistently defined as the rating of perceived exertion (scale of 1-10 with 10 as maximum) multiplied by the minutes of the training session. Both internal and external workloads are assumed to influence injury risk similarly.

- For example, soccer coaches can define external workloads as the total distance covered. If the athlete runs 12 miles in the past 7 days and averaged 10 miles/week over the past 28 days, his ACWR would be 1.2 .

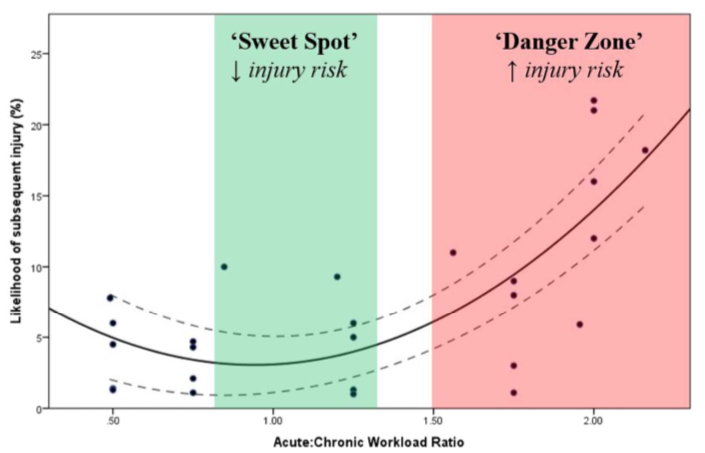

Based on this ratio, researchers have proposed a “sweet spot” (ACWR: 0.8 - 1.3) and “danger zone” (ACWR > 1.5). If the ACWR falls in the “danger zone:, the athlete is at an increased risk for non-contact injuries. If the ACWR is lower, the athlete is at a reduced risk.

The ACWR framework follows the idea of progressive overload (SAID principle). The athlete will improve if she experiences a greater stimulus than accustomed to. But can we recommend a “one size fits all” metric for training load? There is an enormous amount of variation between athletes (genetics, diet, sleep, injury history) which affects injury risk. Also, is the data accurate enough? Measuring the total distance covered in practices/games does not include information on intensity of the distances covered and ignores other types of training (e.g. strength training). Though the simplicity of the ACWR is very attractive, there needs to be strong evidence to support its use.

Timeline of ACWR Research

An editorial by Dr. Tim Gabbett in 2016 introduced the ACWR framework for practical use (the crux of the editorial is the graph from above, which was initially published in a Clinical Analysis by Blanch and Gabbett a few months before).

The editorial encouraged coaches to implement this metric: “To minimise injury risk, practitioners should aim to maintain the acute:chronic workload ratio within a range of approximately 0.8–1.3.” Since its publication, the editorial has been cited over 60 times, including by the International Olympic Committee. Again, we would expect vast amount of research to support such an endorsement. However, the 2016 editorial was limited to the analysis of only two published studies (cricket and rugby) and one unpublished study (Australian rules football):

- 2016: Editorial by Gabbett (preceded by a Clinical Analysis by Blanch and Gabbett)

- 2015: Rugby paper by Hulin et al.

- 2014: Cricket paper by Hulin et al.

- ???: Australian rules football

Given the limited amount of research at the time, we would expect that the results of this research was quite strong for the editorial to make such bold claims.

Evaluation of Cricket and Rugby Studies

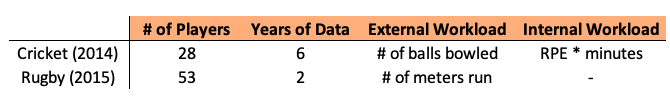

The cricket and rugby studies were retrospective: both considered a data set of training loads and injuries. The cricket study considered 28 fast bowlers over a 6 year period, and the rugby study focused on 53 athletes (no specified position) over 2 years. Researchers then used statistical techniques to look for meaningful relationships. Again, their hypothesis is that ACWRs much greater than 1 put athletes at an increased risk of injury.

Our evaluation can begin with the design of each study. Obviously, the external workloads differ due to the nature of each sport (balls bowled vs. meters covered). Interestingly, only the cricket study presented internal workloads (this could have been due to lack of data availability in the rugby study, but no reason was given). Finally, a more technical distinction between the studies is the categorization of the ACWR buckets. Since the samples sizes were small, it is difficult to evaluate a continuous variable such as ACWR. The solution is to group certain ACWRs into buckets. However, the buckets were not the same between studies (e.g. the cricket paper uses an ACWR bucket of 1.00-1.49 while the rugby study used a bucket of 1.03-1.37).

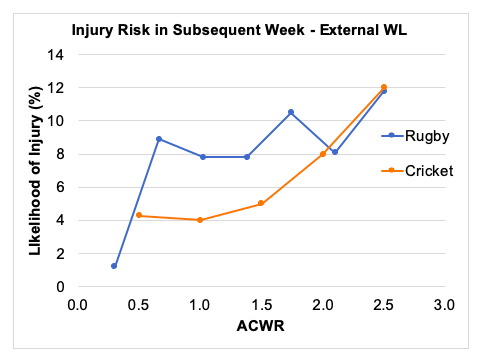

Though the study designs differ, we would still expect to see similar results between them (that greater ACWR lead to greater injury risk). However, when combining the data, it is difficult to see this relationship:

The results of the cricket paper support the hypothesis, but the ACWR-injury risk correlation is not seen as clearly in the rugby study. Though the conflicting evidence did not invalidate the theory, it reflected the need for more research. Instead, the 2016 Editorial was published, and unfortunately, further research has not proven a significant link between ACWR and injury risk. The ACWR may have experienced a path dependence effect: the ease of use behind the ACWR made it attractive and allowed coaches/sports scientists to excuse some inconsistencies in the original research.

Now What?

With regard to training load, coaches may have to continue to operate in a gray area. The idea of progressive overload is still valid, but coaches may need to rely on their experience rather than ACWR to moderate loads. Coaches can address sport-specific issues with proper prehab protocols (such as nordic hamstring curls for soccer players). Finally, proper diet and sleep hygiene are important to remain healthy and reduce injury risk.

One last note is about the trade-off between maximizing performance and reducing injury risk. Depending on their level, athletes can train at either end of this spectrum to achieve their goals (high school athletes likely want to prioritize reducing injury while elite athletes may take a riskier approach).

For a much more thorough analysis this topic, watch Dr. Franco Impellizzeri’s talk at the SportFisio Conference.

Videos